Djinn from the Bronx, Bronx baked, Los Angeles-dwelling genie. Journey with me through past, present and future. Sometimes the magic lamp will work!

Friday, December 27, 2013

The Anxiety of the New

A short entry. I don't hate technology. It just makes me feel very stupid. I bought a new piece of equipment. Between the flurry of e mails thanking me, warranting me and offering me technical support I could not activate the product. I got just so far but not to the finish line. I spent hours. Why? Because I could not accept that as a college and law school graduate this stuff makes me feel like an aged parent. And I become enraged. And I wonder whether when other people call support they stutter with inexperience. And feel the tech on the other side of the line is pitying me. Even laughing. But I strive and as of this moment I shall not give up, I shall visit the Geek Squad tomorrow.

Monday, December 16, 2013

Peter O'Toole: Farewell from a Fan

My cousin, also a great follower of the brooding Irishman with a booming voice that was Peter O'Toole, called his the look of "broken glass." It was as if his inner life was cracking out of him, coming piece by piece from the depth of his soul.

I saw that look for the first time when I was about 8 years old when he was Lawrence of Arabia. He was Lawrence, for he inhabited the role. I was far too young to see such a film about such a complicated historical figure with such a complicated emotional life, but I could not take my eyes off that face nor could I fail to grasp the talent.

He was wild in his youth and well beyond, threatening his health and no doubt shortening his old age by several years. But never did he lose his great capacity to act. To watch The Lion in Winter is to be enthralled--he and his great friend Katherine Hepburn, Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitane tearing each other apart verbally and strategically. To watch him as the broke drunken actor in "My Favorite Year" watching the daughter who does not know him from afar, regret expressed in a slight but telling movement of head, and eye, was to feel something endemic to his real life being.

His crazed creative director in "The Stunt Man" is magical. He could be alternately comedic and gravely dramatic. He could do it in the same movie.

I had the good fortune to see him twice in my life. The first time was in 1987 after I had moved to California, but was back in New York for a visit. He was Professor Higgins in a Broadway production of Pygmalion, along with Sir John Mills and Amanda Plummer, alas the latter a miscast that affected the effectiveness of the production. I had been the recipient of house seats by a friend who knew of my life long admiration of Mr. O'Toole. I could see Mills and O'Toole staged banter spoken with a little spit, gleaming eyes and slight smiles, clearly friends working together. I watched outside the stage door as he signed autographs, looking deeply and unsettlingly into the eyes of the recipient of his largesse. The look of broken glass. Of a passionate, unsettled seeming man. He was at the time in some kind of suit over the custody of his only son, Lorcan, I think. The boy was with him. I sent my second fan letter to the theatre (my first was to James Stewart) a silly expectation that he'd ever get it, or have any interest in it.

It would be more than twenty years, in 2011, before I'd see him again, on this coast. It was after the 2006 film "Venus" in which he played an old actor on his literally last legs having a kind of innocently lasciviously fling with a young woman who had no idea of the man he had been. Turner Classic Movies was having its first film Festival, and O'Toole was going to be at one or two of the films, including Lawrence, that featured him, but more importantly, he was going to be interviewed before a live audience at the Henry Fonda theatre, for broadcast at a later time on the channel. If I saw nothing else at that festival, it was going to be this interview with Robert Osborne.

He was presented to the audience, accompanied at each arm. He was still tall, but frighteningly frail. He walked haltingly. He looked every bit his 79 years or so, and well more.

As Osborne explained to us our roles, he sat quietly, occasionally wiping his mouth, with great discretion, with a handerchief. I wasn't sure he was up to this interview. He was very nearly vacant. A woman to my right complained that she couldn't see him. Couldn't they position him in a manner that would give her a better view? Osborne explained that he had to be in the view of the camera, so no.

And then the show began, the camera was on. Action. And O'Toole reanimated, an easy raconteur about his early life, his acting life, and his life as a happy European in Ireland.

At one point, he turned his head to look in the direction of the woman who had interposed her desire to have him face her. He commented that he wanted to be sure that he was seen on that side of the theatre.

He had been observing us all. I couldn't tell you how delighted I was to be there, and how I wished my companion at the festival had joined me, two once children of Mount Vernon and the Bronx, transplanted to the Hollywood wonderland.

TCM did not show the piece unstil 2012. And it seems that around then, O'Toole announced his retirement from acting.

At the end of "My Favorite Year", the young writer who has been herding the unruly, emotionally wounded, actor watches him being applauded by the audience of the fifties television show. The actor, Alan Swan, dressed as a swashbuckler from one of his old movies, is smiling in acknowledgment and waving his sword. The young writer says, "This is how I'll remember him."

This is how I'll remember Peter O'Toole. I was 8 years old. He was 29, and beautiful.

Saturday, December 7, 2013

The Martyrdoms of Each Day

In 1936 four nuns in Spain were killed for upholding their Catholic faith. Martyrdom in the classic sense. These four women, Mother Aurelia, Sister Aurora, Sister Daria and Sister Agustina were beatified in the country of their death, in October 2013.

Today, I was one among many at St. Basil Church as the local convent of the Sister Servants of Mary, Ministers to the Sick (of whom you know I am fond from earlier entries) celebrating this last stage prior to sainthood.

One of the nuns had written that martyrdom by literally dying is not what is generally required of the average disciple, people like me. In every day, we experience small martyrdoms. I suppose this is a corrollary of what Terese of Lisieux called the Little Way. We take the moments of our lives, good, and bad, and we who believe in our Catholicity, offer those things in union with the sacrifice on the Cross, the condition precedent to the Resurrection that restored the relationship of man and God.

It was cold in Los Angeles today. Don't laugh oh rest of the country. We are having a rare snap, which means that it gets into the forties, sometimes the thirties at night. The church that hosted the celebration is made mostly of stone, a big cavernous place on Wilshire Boulevard. Drafty on a warm day, the cool seeped into your bones through your clothes--not unlike a New York winter's day. It wasn't just me. People were shivering and wrapping their coats around themselves and not finding relief. It was hard to pay attention. Then in the back the sounds of loud voices as the Archbishop was speaking his homily. I went back there when it became intolerable. I wasn't the first. As I opened the inner doors to see the outer doors were wide open, encouraging the cold air to swoop in, I wasn't sure I wouldn't be sharp with those on the other side.

Apparently there was to be a wedding after the celebration of the Beatas, and the bride was having pictures taken. There she was, stock still at the open door in her sleeveless wedding dress, with a photographer, whose voice was likely what had been heard, instructing her.

How could I be sharp with this group. And yet, how thoughtless it seemed they were, disregarding the occasion of another and the reverence due to the Mass. So, I put my hand on the photographer's shoulder and said, "I know that this is a wedding, but there is a Mass inside, if you could lower your voices," or something like that.

I hadn't been the only one to come out.

I realized as I returned to my pew that not only was I distracted, but I was feeling nothing about being there. I wasn't just cold bodily but I was cold as ice emotionally, and if any emotion were to break through it would be irritation and anger. "I feel inconsolable," I thought. Mother Theresa was inconsolable for fifty years. Media pundits concluded that this meant she did not believe in the faith she claimed to have. Those of us practicing our faith, and I emphasize the word "practice", which includes lots of falling and failing, knew that faith is an act of will not a matter of the vagaries of feeling.

I experienced it today, more than intellectually. I had to force myself to pray. And I realized that my absence of feeling was not an absence of belief, although there was a tendency to merge the two.

This was a small martyrdom. Tiny, indeed, but still something to bear with a recognition that I was not abandoned, even when it felt to be so. I have never been hugely attracted to those saints who seek martyrdom. But I think that I ought to be attracted to those who have it thrust upon them, and accept it with equanimity. May I never face that, but then it seems it should be a piece of cake to accept a little cold, a little noise, and a lack of feeling consoled.

Today, I was one among many at St. Basil Church as the local convent of the Sister Servants of Mary, Ministers to the Sick (of whom you know I am fond from earlier entries) celebrating this last stage prior to sainthood.

One of the nuns had written that martyrdom by literally dying is not what is generally required of the average disciple, people like me. In every day, we experience small martyrdoms. I suppose this is a corrollary of what Terese of Lisieux called the Little Way. We take the moments of our lives, good, and bad, and we who believe in our Catholicity, offer those things in union with the sacrifice on the Cross, the condition precedent to the Resurrection that restored the relationship of man and God.

It was cold in Los Angeles today. Don't laugh oh rest of the country. We are having a rare snap, which means that it gets into the forties, sometimes the thirties at night. The church that hosted the celebration is made mostly of stone, a big cavernous place on Wilshire Boulevard. Drafty on a warm day, the cool seeped into your bones through your clothes--not unlike a New York winter's day. It wasn't just me. People were shivering and wrapping their coats around themselves and not finding relief. It was hard to pay attention. Then in the back the sounds of loud voices as the Archbishop was speaking his homily. I went back there when it became intolerable. I wasn't the first. As I opened the inner doors to see the outer doors were wide open, encouraging the cold air to swoop in, I wasn't sure I wouldn't be sharp with those on the other side.

Apparently there was to be a wedding after the celebration of the Beatas, and the bride was having pictures taken. There she was, stock still at the open door in her sleeveless wedding dress, with a photographer, whose voice was likely what had been heard, instructing her.

How could I be sharp with this group. And yet, how thoughtless it seemed they were, disregarding the occasion of another and the reverence due to the Mass. So, I put my hand on the photographer's shoulder and said, "I know that this is a wedding, but there is a Mass inside, if you could lower your voices," or something like that.

I hadn't been the only one to come out.

I realized as I returned to my pew that not only was I distracted, but I was feeling nothing about being there. I wasn't just cold bodily but I was cold as ice emotionally, and if any emotion were to break through it would be irritation and anger. "I feel inconsolable," I thought. Mother Theresa was inconsolable for fifty years. Media pundits concluded that this meant she did not believe in the faith she claimed to have. Those of us practicing our faith, and I emphasize the word "practice", which includes lots of falling and failing, knew that faith is an act of will not a matter of the vagaries of feeling.

I experienced it today, more than intellectually. I had to force myself to pray. And I realized that my absence of feeling was not an absence of belief, although there was a tendency to merge the two.

This was a small martyrdom. Tiny, indeed, but still something to bear with a recognition that I was not abandoned, even when it felt to be so. I have never been hugely attracted to those saints who seek martyrdom. But I think that I ought to be attracted to those who have it thrust upon them, and accept it with equanimity. May I never face that, but then it seems it should be a piece of cake to accept a little cold, a little noise, and a lack of feeling consoled.

Sunday, September 22, 2013

George Parnassus, Priest, Pray for Him

I had been in Los Angeles for about two years. For many years before that, I had experienced the "twitch upon the thread" of my lapsed Catholicism. It was a matter of time before I came back home, I knew. But, as I sat in Mirabelle Restaurant on Sunset Boulevard with an earlier transplanted east coast friend who had remained a practicing Catholic, I had no idea that time was upon me.

Typical of the sixties generation of which I was otherwise an awkward, even unsuccessful part, I had been away from the Church for thirteen years by then. The reasons were less about the church than my Judas Iscariot like lack of trust in God, although of course I rationalized with the best of lapsi illogic.

"I'm thinking of going back to Church," I said, or something very much like it.

"There's a little church around the corner," she said, or something very much like it.

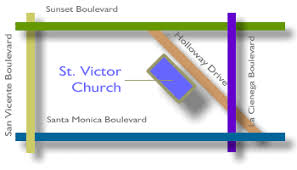

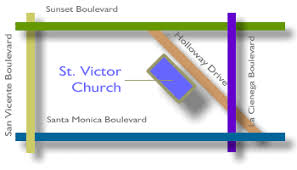

'Around the corner' was a little street, in between Sunset and Santa Monica, that I had no idea existed, Holloway Drive, on which stood a small edifice which had the name of a church I had never heard of, St. Victor. St. Victor was a Pope, it turns out in the early part of Christianity, from Africa. My friend was then attending this parish, although shortly after, she would move to Santa Monica.

I think it was a weekday, in November 1983, around the Thanksgiving holidays and the anniversary of my mother's death that I walked into a sparsely attended 12:10 daily Mass. A slight but straight, darkly even medievally handsome middle aged priest was celebrating the Mass.

As he preached his homily, he proclaimed with committed authority that "God was knocking on our hearts". As I sat in the shadows of the very last pew I felt as if that priest's deep set brooding eyes were boring into mine as he spoke. Impossible. But I couldn't deny that it felt as if Someone were indeed knocking on my heart, and that, as the priest whom I came to know to be Monsignor George J. Parnassus, would often say, there were no accidents with God.

I began to attend Mass, without recourse to the other sacraments, especially that of Reconciliation. I did that for three years. Somewhere in there, I approached the Monsignor for the first time. It was not a propitious encounter.

I wanted to bring used clothes to the Church for the yearly rummage sale, but there was no one around to ask about the proper depository of donations, except Monsignor. With stern deliberation he was wending his way down the then slim terrace from the sacristy, to go through the side door and through the church to the rectory. He was brusque. "I'm on the way to an appointment," he said, and he wasn't stopping for my question.

The Djinn who walked away from the practice of her faith as a teenager had become something of an adult. I concluded two things at that moment. The momentary failure of the distracted human Monsignor was not a reason to leave St. Victor's and avoid the centrality of the God Present in the Eucharist, although I was somewhat vague on my theology in those days. And, for some reason, I knew that this priest with an edge was someone whose respect I wanted to earn. There was probably some psychological transference, as he reminded me a great deal of my mother, by now dead at least ten years, and equally of my father, who shared with him a part Greek heritage. I had a spiritual, and a very earthly reason to stay, both.

It was about 1986 that I decided to become a full fledged member of the parish and share in the panoply of the Sacraments available to me. I went to some parish meeting. There was Monsignor, with another man, who would also become a lifelong friend, respectively conducting the meeting. After the meeting concluded, I sat on the edge of the stage in the meeting room/auditorium. Monsignor was eager to hear about me, what I did (I had just begun my job at the State Bar that very year), and where I came from, and what I thought about this and that. It was brief, but it was encouraging. We seemed to like each other.

Having apparently assessed me and my motivations, he began to ask me to assist in parish activities. St. Victor's was, and remains, something of an interesting bridge between the days of pre-Vatican II and post-Vatican II and from my perch from the pew, the best of both. People called it, and still call it a "gay-friendly" parish. That misses the point. What it was and has always remained, under the helm of Monsignor Parnassus to today, is a place for us, sinners all, seeking to practice our faith without compromise, recognizing the limits of our fallen human nature and seeking forgiveness for our endless failures through which God continues to love us. We were to conform to God, not God to us. Perhaps that is why Monsignor preached so often on the Confession and I think he used the phrase interchangeably with that of "Reconciliation." He would say, "I notice how almost everyone goes to Communion each and every Sunday, but there are few at the Confessional on a Saturday." He would urge us to lay ourselves before our God, with humility. Always with a humility, which he noted time and time again, eluded him and for which he prayed constantly. For himself, and for us, together.

I didn't seek to confess with Monsignor as mediator very often. I recently told a priest, Fr. Wolfe, from another parish to whom I go to Confession when he happened to meet me at my own "You know, don't you, that we (Catholics) often don't go to confession at their own parishes?" He knew. It had been true even in his day. But every once in a while, with much on my mind and soul, I would break that rule and sought out Monsignor Parnassus, by appointment to discuss a sin that weighed on my mind, that was surely separating me in my walk with God. People who might have been put off by Monsignor's austere demeanor, a defense, he would once tell me, when he became a teacher at school and had to deal with students, for which he felt no internal confidence, missed the most precious of experiences of reconciliation with God. He spoke with both kindness, empathy and theological depth , and it was as if, something that I felt true of his homilies, in those moments God was speaking through this complex man, especially.

My father, a lapsed Greek Orthodox, who came to Mass on Christmas and Easter mostly to share the holiday with me, and to hear me in my role, as of about 1987, as substitute lector, and then later as a regular lector, took an immediate shine to Monsignor, as did Monsignor to him. Both their fathers had been the immigrants from Greece. Both their mothers, Dad's of Italian heritage, and Monsignor's of Mexican heritage, were American born. Both fathers had had something of a similar beginning although unlike my grandfather, Monsignor's father had found success and apparently wealth as a boxing promoter, so well known that today he is in the Boxing Hall of Fame. He was also called George. He had died in 1975, only a year or so after my mother did. So, whenever there were parish dinners, my father was present, often at Monsignor's table with some of the rest of his family, Monsignor's brother Bill, and Bill's wife Gloria.

My father had an intellectual interest in all religion, saying often that IF he were to practice one, it would either be as a Jew or as a Catholic. But he would not commit to anything--not even whether he actually believed in God in the first instance. Anyone who knew my dad knew that he would become vague on the subject and, as I used to say to him, a little like the narrator in "Our Town" observing the rest of humanity, as if he were not a member of it. I'd shake my head in frustration. When Dad was about to have his four part by pass surgery in 1989, having checked the box on the hospital intake form reflecting he had no religion, I ran to Monsignor for advice. What should I do? In the same way that Monica was advised regarding her son, Augustine, Monsignor advised me, daughter of Constantine, "Leave him alone. Just pray." Dad and I would have our skirmishes after his successful surgery and his rocky emotional recovery about Catholicism. After one of Monsignor's magnificent homilies, as usual delivered without notes- my father said, "I didn't hear or see anything startling." Frustrated, I said, "If Jesus the Lord stood behind Monsignor transfigured during the homily, I think you'd still say that!" but Dad kept coming. Perhaps it was some of the social occasions, dinners at the rectory with various parishioners, and a dinner or two at restaurants, where Monsignor would try to penetrate my father's religious wall, that greased the wheel.

Monsignor was an impressario, not of boxing, but of preaching God's word. And my father protested, but stayed close to me, the Church, and Monsignor.

Dad was 85, having had a bit of wine with dinner, when he called me, and said that he wanted to become a Catholic--to make it "easier" for me was his cryptic rationale. I knew it was related to his age and disposition after death. It would be easier for me if I could bury him out of St. Victor. Was it only that? I don't know. I will never really know. What did Monsignor say to me over a dinner with several people, once, at Sofi, a Greek Restaurant. It is prideful for us, as Christians, to want to see ourselves hit a home run spiritually speaking. I wanted my father to have some kind of Pauline like conversion on Holloway Drive, simply because of my and our attendance at this Church, but however it happened, it brought Dad to God, and I need not have anything to do with it.

Dad had a condition for his training as a Catholic. It had to be Monsignor Parnassus to conduct it.

Knowing both men, each close to the vest, both capable of conviviality, a secret kindness and sharp reproach of themselves and others, I wished I could be a fly on the wall. My father would argue every point of theology, and ask questions to which he really was not seeking an answer. I couldn't imagine Monsignor being patient with him. I certainly wasn't. And yet, one day, somewhat before the Easter Vigil in 2003, in the sacristy before the 12:15 Mass which by now I had attended as a lector since 1987, with a brief self imposed respite for one year in the late 1990s, Monsignor said Dad would be received into the Church.

By then Monsignor had retired as pastor, his mother, a grand dame to whom he always offered a tender deference, had died, his own health having been long compromised by what I have always believed to be a botched surgery on his spine in the early 1990s (he never said to me; Dad once told me he had vouchsafed the story to him. No surprise. Dad seemed to have the role of a second older brother to Monsignor. It was somewhere between informal and formal. Words did not get spoken about it, as befitted men of their generations. But when it came time for dad to be received, Monsignor stood up from the side of the altar, and presided over this one reception. I was Dad's sponsor. I saw the tears welling up in the eyes of the servers who knew us all, as they welled up in mine. And Monsignor, who was not given to hugging, took my father, who also avoided physical or verbal sentiment, into his arms.

Two difficult determined, fascinating and decent men, my two fathers, in their respective ways I have come to realize, one of blood, one of spirit, each contributing to the person I had become.

To gain their respect, one had to work very hard, and sometimes still not know if the line had been met, no, in truth, pretty sure that the line hadn't been met. Which only meant that I wanted to try all the more, sometimes with a level of enormous frustration that still did not deter.

When Dad was losing the battle of sepsis in the hospital in April 2008, connected to breathing apparatus and pumped with vasopressors to keep up his blood pressure, I met with Monsignor and talked about the line between ordinary and necessary care and extraordinary efforts. Monsignor helped me during those days navigate that treacherous tightrope and I was impressed by his certainty of God helping me to the right decision. "Will what they are doing improve his chances?" he told me to ask the doctors. Dad's chances could not be improved. He died on April 8, having survived to his 90th birthday without ever having had to leave his home or lose his independence.

Monsignor was by then quite physically impaired, but still ambulatory by cane and it was he who said the homily at Dad's funeral which was instructive religiously, as required by the occasion, but enormously personal in its clear affection for my dad, so much so that more than one attendee noted never having heard one so warm.

After dad died, Monsignor took me under his wing, as I knew he took so many of us at St. Victor's, one of his spiritual daughters and sons. There were many invitations to the large dinners at the rectory, and many group outings to his last favorite restaurant, Lucques. He still could drink a little, mostly now Proseco, less hard on his stomach. He could attend these moments with parish family members in mufti, that is, without the collar which he always wore with honor, but which sometimes caused people to distance themselves.

After I lost my job in 2011, I planned on increasing my attendance at Mass, but not necessarily to go every day. God, of course, had his plans, and I began attending daily, and then helping out, and then bringing Communion, mostly every day to Monsignor. It was never easy for me. When he was having a difficult day, he would ask that Our Lord be left on the personal altar he maintained, and where, for some time when he was able, he had said Mass privately. He was not going "gently into that good night" and he realized that he required God's help to temper his temper, and to bring him to that humility which eluded him, he acknowledged in prayer after prayer in dealing with the suffering that had been visited upon him. I often found myself joining quietly in that prayer, for humility I once said to him, "is indeed a tough nut to crack." I always felt that there was some secret sadness in him as I felt existed in my father before him. Perhaps we all have our secret sorrows, never to be discovered by those who love us.

There were times I thought, he's giving up after a hospital stay. But then, he'd be back in the rectory and orchestrating a project, the last something he called Our Lady of the Well of Nazareth, by which he worked with Catholic Relief Services to make and arrange donations for the building and rehabilitation of wells in drought prone and drought striken areas. Particularly he became interested in East Africa. He had research done. He did some himself somehow. He summoned several of us to his bedside to discuss events to raise money and to dictate letters. I became his scrivener and his secretary.

He became discouraged for a while at what he perceived to be a lack of sufficient interest in the project, although many had in fact donated, probably because he asked it. I would remind him that the economy was bad, as he himself had recognized, and that people had their own charities. I understood their problem. I had my own, for which I did little enough, the Sister Servants of Mary. We who assisted wanted him to be at the center of the fundraising, to use his name, to make him the honoree at some event, even if he could only attend for a short time. He resisted, even angrily with a resounding "No!" It was Our Lady who was to be the center, the one honored.

And then, he decided to dictate a letter, and put it on tape. I stood by his bed tape in hand at his request as he did what was always so amazing, create a homily and an appeal all at once, with beginning, middle and end perfect and affecting, a spiritual Vincent Lombardi.

In his voice: "I myself was trying to see the future that I had with this work and because of illness and old age and a certain amount of tiredness I was very disappointed in myself and in the project and wanted to simply withdraw from it altogether. But then I was given a report about what had actually been done. . .and this was a startling statement of what can be done by the Blessed Mother when she is asked to help her children. And I believe she was telling me also in a very clear way that I must not withdraw from it, that I must keep on even though I am old and ill. She can use an instrument like me to do her work, but I must have a pure heart and a clear commitment so I am resolved to do all that I can to continue in this. I am speaking to you now in this letter to tell you that you must consider that this is her work and that you must not say no to her, you must not turn a deaf ear to her call to help her children, but to do what you can with comittment with spreading the word about this and with your personal sacrifices for Our Lady of the Well of Nazareth." He ended, as follows, as only he could, with "Period. That will be the first letter."

.jpg) That was probably at the end of 2012 or the beginning of 2013. He had fewer good days after that. A few of us were able to bring him Communion, and he was able to take Our Lord right up to the Thursday before the Saturday he died. Monsignor Murphy gave him the Anointing of the Sick. He sought the Sacrament of Reconciliation often during his illness. He reminded me that he did not want anyone to say after he died that he was surely in heaven. He was certain he'd be spending time in Purgatory, so that he could be fully purged of the effects of sin on earth and made pristine before being in the Presence of God.

That was probably at the end of 2012 or the beginning of 2013. He had fewer good days after that. A few of us were able to bring him Communion, and he was able to take Our Lord right up to the Thursday before the Saturday he died. Monsignor Murphy gave him the Anointing of the Sick. He sought the Sacrament of Reconciliation often during his illness. He reminded me that he did not want anyone to say after he died that he was surely in heaven. He was certain he'd be spending time in Purgatory, so that he could be fully purged of the effects of sin on earth and made pristine before being in the Presence of God.

He was very clear that the souls of the dead must be given our prayers. He asked that on his marker, it say, "George Parnassus, Priest" with the dates of his birth and death and ordination, followed by, "Pray for Him." It is probably no accident that the prayer card for his ordination asked the same thing, "Pray for me."

Typical of the sixties generation of which I was otherwise an awkward, even unsuccessful part, I had been away from the Church for thirteen years by then. The reasons were less about the church than my Judas Iscariot like lack of trust in God, although of course I rationalized with the best of lapsi illogic.

"I'm thinking of going back to Church," I said, or something very much like it.

"There's a little church around the corner," she said, or something very much like it.

'Around the corner' was a little street, in between Sunset and Santa Monica, that I had no idea existed, Holloway Drive, on which stood a small edifice which had the name of a church I had never heard of, St. Victor. St. Victor was a Pope, it turns out in the early part of Christianity, from Africa. My friend was then attending this parish, although shortly after, she would move to Santa Monica.

I think it was a weekday, in November 1983, around the Thanksgiving holidays and the anniversary of my mother's death that I walked into a sparsely attended 12:10 daily Mass. A slight but straight, darkly even medievally handsome middle aged priest was celebrating the Mass.

As he preached his homily, he proclaimed with committed authority that "God was knocking on our hearts". As I sat in the shadows of the very last pew I felt as if that priest's deep set brooding eyes were boring into mine as he spoke. Impossible. But I couldn't deny that it felt as if Someone were indeed knocking on my heart, and that, as the priest whom I came to know to be Monsignor George J. Parnassus, would often say, there were no accidents with God.

I began to attend Mass, without recourse to the other sacraments, especially that of Reconciliation. I did that for three years. Somewhere in there, I approached the Monsignor for the first time. It was not a propitious encounter.

I wanted to bring used clothes to the Church for the yearly rummage sale, but there was no one around to ask about the proper depository of donations, except Monsignor. With stern deliberation he was wending his way down the then slim terrace from the sacristy, to go through the side door and through the church to the rectory. He was brusque. "I'm on the way to an appointment," he said, and he wasn't stopping for my question.

The Djinn who walked away from the practice of her faith as a teenager had become something of an adult. I concluded two things at that moment. The momentary failure of the distracted human Monsignor was not a reason to leave St. Victor's and avoid the centrality of the God Present in the Eucharist, although I was somewhat vague on my theology in those days. And, for some reason, I knew that this priest with an edge was someone whose respect I wanted to earn. There was probably some psychological transference, as he reminded me a great deal of my mother, by now dead at least ten years, and equally of my father, who shared with him a part Greek heritage. I had a spiritual, and a very earthly reason to stay, both.

It was about 1986 that I decided to become a full fledged member of the parish and share in the panoply of the Sacraments available to me. I went to some parish meeting. There was Monsignor, with another man, who would also become a lifelong friend, respectively conducting the meeting. After the meeting concluded, I sat on the edge of the stage in the meeting room/auditorium. Monsignor was eager to hear about me, what I did (I had just begun my job at the State Bar that very year), and where I came from, and what I thought about this and that. It was brief, but it was encouraging. We seemed to like each other.

Having apparently assessed me and my motivations, he began to ask me to assist in parish activities. St. Victor's was, and remains, something of an interesting bridge between the days of pre-Vatican II and post-Vatican II and from my perch from the pew, the best of both. People called it, and still call it a "gay-friendly" parish. That misses the point. What it was and has always remained, under the helm of Monsignor Parnassus to today, is a place for us, sinners all, seeking to practice our faith without compromise, recognizing the limits of our fallen human nature and seeking forgiveness for our endless failures through which God continues to love us. We were to conform to God, not God to us. Perhaps that is why Monsignor preached so often on the Confession and I think he used the phrase interchangeably with that of "Reconciliation." He would say, "I notice how almost everyone goes to Communion each and every Sunday, but there are few at the Confessional on a Saturday." He would urge us to lay ourselves before our God, with humility. Always with a humility, which he noted time and time again, eluded him and for which he prayed constantly. For himself, and for us, together.

I didn't seek to confess with Monsignor as mediator very often. I recently told a priest, Fr. Wolfe, from another parish to whom I go to Confession when he happened to meet me at my own "You know, don't you, that we (Catholics) often don't go to confession at their own parishes?" He knew. It had been true even in his day. But every once in a while, with much on my mind and soul, I would break that rule and sought out Monsignor Parnassus, by appointment to discuss a sin that weighed on my mind, that was surely separating me in my walk with God. People who might have been put off by Monsignor's austere demeanor, a defense, he would once tell me, when he became a teacher at school and had to deal with students, for which he felt no internal confidence, missed the most precious of experiences of reconciliation with God. He spoke with both kindness, empathy and theological depth , and it was as if, something that I felt true of his homilies, in those moments God was speaking through this complex man, especially.

My father, a lapsed Greek Orthodox, who came to Mass on Christmas and Easter mostly to share the holiday with me, and to hear me in my role, as of about 1987, as substitute lector, and then later as a regular lector, took an immediate shine to Monsignor, as did Monsignor to him. Both their fathers had been the immigrants from Greece. Both their mothers, Dad's of Italian heritage, and Monsignor's of Mexican heritage, were American born. Both fathers had had something of a similar beginning although unlike my grandfather, Monsignor's father had found success and apparently wealth as a boxing promoter, so well known that today he is in the Boxing Hall of Fame. He was also called George. He had died in 1975, only a year or so after my mother did. So, whenever there were parish dinners, my father was present, often at Monsignor's table with some of the rest of his family, Monsignor's brother Bill, and Bill's wife Gloria.

My father had an intellectual interest in all religion, saying often that IF he were to practice one, it would either be as a Jew or as a Catholic. But he would not commit to anything--not even whether he actually believed in God in the first instance. Anyone who knew my dad knew that he would become vague on the subject and, as I used to say to him, a little like the narrator in "Our Town" observing the rest of humanity, as if he were not a member of it. I'd shake my head in frustration. When Dad was about to have his four part by pass surgery in 1989, having checked the box on the hospital intake form reflecting he had no religion, I ran to Monsignor for advice. What should I do? In the same way that Monica was advised regarding her son, Augustine, Monsignor advised me, daughter of Constantine, "Leave him alone. Just pray." Dad and I would have our skirmishes after his successful surgery and his rocky emotional recovery about Catholicism. After one of Monsignor's magnificent homilies, as usual delivered without notes- my father said, "I didn't hear or see anything startling." Frustrated, I said, "If Jesus the Lord stood behind Monsignor transfigured during the homily, I think you'd still say that!" but Dad kept coming. Perhaps it was some of the social occasions, dinners at the rectory with various parishioners, and a dinner or two at restaurants, where Monsignor would try to penetrate my father's religious wall, that greased the wheel.

Monsignor was an impressario, not of boxing, but of preaching God's word. And my father protested, but stayed close to me, the Church, and Monsignor.

Dad was 85, having had a bit of wine with dinner, when he called me, and said that he wanted to become a Catholic--to make it "easier" for me was his cryptic rationale. I knew it was related to his age and disposition after death. It would be easier for me if I could bury him out of St. Victor. Was it only that? I don't know. I will never really know. What did Monsignor say to me over a dinner with several people, once, at Sofi, a Greek Restaurant. It is prideful for us, as Christians, to want to see ourselves hit a home run spiritually speaking. I wanted my father to have some kind of Pauline like conversion on Holloway Drive, simply because of my and our attendance at this Church, but however it happened, it brought Dad to God, and I need not have anything to do with it.

Dad had a condition for his training as a Catholic. It had to be Monsignor Parnassus to conduct it.

Knowing both men, each close to the vest, both capable of conviviality, a secret kindness and sharp reproach of themselves and others, I wished I could be a fly on the wall. My father would argue every point of theology, and ask questions to which he really was not seeking an answer. I couldn't imagine Monsignor being patient with him. I certainly wasn't. And yet, one day, somewhat before the Easter Vigil in 2003, in the sacristy before the 12:15 Mass which by now I had attended as a lector since 1987, with a brief self imposed respite for one year in the late 1990s, Monsignor said Dad would be received into the Church.

By then Monsignor had retired as pastor, his mother, a grand dame to whom he always offered a tender deference, had died, his own health having been long compromised by what I have always believed to be a botched surgery on his spine in the early 1990s (he never said to me; Dad once told me he had vouchsafed the story to him. No surprise. Dad seemed to have the role of a second older brother to Monsignor. It was somewhere between informal and formal. Words did not get spoken about it, as befitted men of their generations. But when it came time for dad to be received, Monsignor stood up from the side of the altar, and presided over this one reception. I was Dad's sponsor. I saw the tears welling up in the eyes of the servers who knew us all, as they welled up in mine. And Monsignor, who was not given to hugging, took my father, who also avoided physical or verbal sentiment, into his arms.

Two difficult determined, fascinating and decent men, my two fathers, in their respective ways I have come to realize, one of blood, one of spirit, each contributing to the person I had become.

To gain their respect, one had to work very hard, and sometimes still not know if the line had been met, no, in truth, pretty sure that the line hadn't been met. Which only meant that I wanted to try all the more, sometimes with a level of enormous frustration that still did not deter.

When Dad was losing the battle of sepsis in the hospital in April 2008, connected to breathing apparatus and pumped with vasopressors to keep up his blood pressure, I met with Monsignor and talked about the line between ordinary and necessary care and extraordinary efforts. Monsignor helped me during those days navigate that treacherous tightrope and I was impressed by his certainty of God helping me to the right decision. "Will what they are doing improve his chances?" he told me to ask the doctors. Dad's chances could not be improved. He died on April 8, having survived to his 90th birthday without ever having had to leave his home or lose his independence.

Monsignor was by then quite physically impaired, but still ambulatory by cane and it was he who said the homily at Dad's funeral which was instructive religiously, as required by the occasion, but enormously personal in its clear affection for my dad, so much so that more than one attendee noted never having heard one so warm.

After dad died, Monsignor took me under his wing, as I knew he took so many of us at St. Victor's, one of his spiritual daughters and sons. There were many invitations to the large dinners at the rectory, and many group outings to his last favorite restaurant, Lucques. He still could drink a little, mostly now Proseco, less hard on his stomach. He could attend these moments with parish family members in mufti, that is, without the collar which he always wore with honor, but which sometimes caused people to distance themselves.

After I lost my job in 2011, I planned on increasing my attendance at Mass, but not necessarily to go every day. God, of course, had his plans, and I began attending daily, and then helping out, and then bringing Communion, mostly every day to Monsignor. It was never easy for me. When he was having a difficult day, he would ask that Our Lord be left on the personal altar he maintained, and where, for some time when he was able, he had said Mass privately. He was not going "gently into that good night" and he realized that he required God's help to temper his temper, and to bring him to that humility which eluded him, he acknowledged in prayer after prayer in dealing with the suffering that had been visited upon him. I often found myself joining quietly in that prayer, for humility I once said to him, "is indeed a tough nut to crack." I always felt that there was some secret sadness in him as I felt existed in my father before him. Perhaps we all have our secret sorrows, never to be discovered by those who love us.

There were times I thought, he's giving up after a hospital stay. But then, he'd be back in the rectory and orchestrating a project, the last something he called Our Lady of the Well of Nazareth, by which he worked with Catholic Relief Services to make and arrange donations for the building and rehabilitation of wells in drought prone and drought striken areas. Particularly he became interested in East Africa. He had research done. He did some himself somehow. He summoned several of us to his bedside to discuss events to raise money and to dictate letters. I became his scrivener and his secretary.

He became discouraged for a while at what he perceived to be a lack of sufficient interest in the project, although many had in fact donated, probably because he asked it. I would remind him that the economy was bad, as he himself had recognized, and that people had their own charities. I understood their problem. I had my own, for which I did little enough, the Sister Servants of Mary. We who assisted wanted him to be at the center of the fundraising, to use his name, to make him the honoree at some event, even if he could only attend for a short time. He resisted, even angrily with a resounding "No!" It was Our Lady who was to be the center, the one honored.

And then, he decided to dictate a letter, and put it on tape. I stood by his bed tape in hand at his request as he did what was always so amazing, create a homily and an appeal all at once, with beginning, middle and end perfect and affecting, a spiritual Vincent Lombardi.

In his voice: "I myself was trying to see the future that I had with this work and because of illness and old age and a certain amount of tiredness I was very disappointed in myself and in the project and wanted to simply withdraw from it altogether. But then I was given a report about what had actually been done. . .and this was a startling statement of what can be done by the Blessed Mother when she is asked to help her children. And I believe she was telling me also in a very clear way that I must not withdraw from it, that I must keep on even though I am old and ill. She can use an instrument like me to do her work, but I must have a pure heart and a clear commitment so I am resolved to do all that I can to continue in this. I am speaking to you now in this letter to tell you that you must consider that this is her work and that you must not say no to her, you must not turn a deaf ear to her call to help her children, but to do what you can with comittment with spreading the word about this and with your personal sacrifices for Our Lady of the Well of Nazareth." He ended, as follows, as only he could, with "Period. That will be the first letter."

.jpg) That was probably at the end of 2012 or the beginning of 2013. He had fewer good days after that. A few of us were able to bring him Communion, and he was able to take Our Lord right up to the Thursday before the Saturday he died. Monsignor Murphy gave him the Anointing of the Sick. He sought the Sacrament of Reconciliation often during his illness. He reminded me that he did not want anyone to say after he died that he was surely in heaven. He was certain he'd be spending time in Purgatory, so that he could be fully purged of the effects of sin on earth and made pristine before being in the Presence of God.

That was probably at the end of 2012 or the beginning of 2013. He had fewer good days after that. A few of us were able to bring him Communion, and he was able to take Our Lord right up to the Thursday before the Saturday he died. Monsignor Murphy gave him the Anointing of the Sick. He sought the Sacrament of Reconciliation often during his illness. He reminded me that he did not want anyone to say after he died that he was surely in heaven. He was certain he'd be spending time in Purgatory, so that he could be fully purged of the effects of sin on earth and made pristine before being in the Presence of God. He was very clear that the souls of the dead must be given our prayers. He asked that on his marker, it say, "George Parnassus, Priest" with the dates of his birth and death and ordination, followed by, "Pray for Him." It is probably no accident that the prayer card for his ordination asked the same thing, "Pray for me."

Monday, September 9, 2013

The Last Few Days in England

I have been away from writing. The reason will be the subject of an entry soon, I hope. But, in the meantime, I wish to complete the tale of my early summer sojourn in the land of Will, Shakespeare that is.

Where was I? Just finishing out my trip to Oxford, and Littlemore. And on to Portsmouth, by bus again, through that town in which the Titanic berthed before her fateful encounter with an iceberg. Southampton. Portsmouth reminded me of any port in New York Harbor, but this one had its special attractions, the HMS Victory upon which Horatio Nelson died in great honor, and the once flagship of Henry the VIII which sank in 1545, the Mary Rose.

I have been on the USS Missouri and been amazed, but to be on a ship that sailed in the early 19th century, to see what men endured on the high seas, in sheer size and endless cannon, was astonishing. Even in the sick bay, there were cannon poking out the square holes aimed at enemies of the state and marauders of the ocean. To stand on the upper deck, next to the rigging was a pleasure and an honor.

And next door, the newly opened exhibit of the Mary Rose. Only half the ship survived the hundreds of years. A ship that Henry saw sink, no doubt, from the shore. And a few bones, literally. Of several men and a dog named given the name of Hatch by those who brought the rig up. Why did the men die? They died because the same rope and material used to keep enemies off the ship prevented those on the ship from escaping as the Mary Rose sank. That's what they think, at least, speculate. The Mary Rose, like perhaps the later Victory, was a mini-city (but no cruiseship). Animals, clothes, mugs, arrows, cannon, musket, and men, all men, men with bad teeth, and brittle bones from too much backbreaking work, old at 30, serving his Majesty, The King.

This is a section of the Mary Rose. For 17 years, the hull has been sprayed with a kind of polymer to keep it from crumbling. For another few, it will be dried out and then the piping will be removed so people can see the hull close up.

This is a section of the Mary Rose. For 17 years, the hull has been sprayed with a kind of polymer to keep it from crumbling. For another few, it will be dried out and then the piping will be removed so people can see the hull close up.

The figure just above was forensically created from the skeleton above it. This was a tall man, unusual for the time, at 6 foot 2. An archer we are told. To stand in front of him is to feel a chill of the past and a sense of sadness for the loss of such a young man.

The carving is they think the name of the cook.

Again, so much to see and only a quick if still amazing surveying. I was exhausted and Heather and I retired to a pub, after a newly restored B-52 or something flew low above us, for a snack. I had a salad and a pint; she had a burrito, which amused me as we were about as far from the home of the burrito as could be possible here on the seaside of Portsmouth.

Then we took a train back to London--a cleaner version of Amtrak, with nice tables upon which to read the Guardian, or some such paper. I spent the time looking out the window at the suburbs, many of them not unlike places along the Hudson. Big houses and restaurants. It was after 8 thirty when we got back to the station and we were grateful for the cab to take us back to the Penn Club.

I had only one more full day in this astounding town in which I found myself so comfortable, and I would spend much of it walking and meeting up with Denise at her club, eating a lovely early dinner and then attending Mass at the Farm Street Catholic Church nearby, not far from Berkeley Square. And then we, she the lady of a certain age and me a somewhat younger lady of a certain age, joined the young English up and comers at a nearby pub. I had two pints, while she drank ginger ale, and realized that the English Beer is far more with alcoholic content than the average American beer.

The next day I would arrive at British Airways to find that they were overbooked, but somehow I managed to get on the flight, and on a bulkhead, tasking two Lorazepams and not being slightly calm as a result. Hypervigilant though I remained for 10 plus hours, it was a lovely quiet flight.

I was delighted to arrive home safely so I could share a few of the moments which so entranced me. It has taken me nearly the whole summer to write of the trip, and now, somehow, it seems so long ago.

I shall go back, I believe and this time, branch out to other places, like Ireland and France. Ireland first, I should think, where there are some members of my mother's family, we unknown to each other for now. I had the chance to go just this month, but there were many other things which made that difficult, and so I did not. The loss of a good friend and mentor, which was sad. And a new pair of 20 20 eyes (mine) which was a great revelation.

More to come from Los Angeles. . . .by way of Djinn from the Bronx!

Where was I? Just finishing out my trip to Oxford, and Littlemore. And on to Portsmouth, by bus again, through that town in which the Titanic berthed before her fateful encounter with an iceberg. Southampton. Portsmouth reminded me of any port in New York Harbor, but this one had its special attractions, the HMS Victory upon which Horatio Nelson died in great honor, and the once flagship of Henry the VIII which sank in 1545, the Mary Rose.

I have been on the USS Missouri and been amazed, but to be on a ship that sailed in the early 19th century, to see what men endured on the high seas, in sheer size and endless cannon, was astonishing. Even in the sick bay, there were cannon poking out the square holes aimed at enemies of the state and marauders of the ocean. To stand on the upper deck, next to the rigging was a pleasure and an honor.

And next door, the newly opened exhibit of the Mary Rose. Only half the ship survived the hundreds of years. A ship that Henry saw sink, no doubt, from the shore. And a few bones, literally. Of several men and a dog named given the name of Hatch by those who brought the rig up. Why did the men die? They died because the same rope and material used to keep enemies off the ship prevented those on the ship from escaping as the Mary Rose sank. That's what they think, at least, speculate. The Mary Rose, like perhaps the later Victory, was a mini-city (but no cruiseship). Animals, clothes, mugs, arrows, cannon, musket, and men, all men, men with bad teeth, and brittle bones from too much backbreaking work, old at 30, serving his Majesty, The King.

This is a section of the Mary Rose. For 17 years, the hull has been sprayed with a kind of polymer to keep it from crumbling. For another few, it will be dried out and then the piping will be removed so people can see the hull close up.

This is a section of the Mary Rose. For 17 years, the hull has been sprayed with a kind of polymer to keep it from crumbling. For another few, it will be dried out and then the piping will be removed so people can see the hull close up.The figure just above was forensically created from the skeleton above it. This was a tall man, unusual for the time, at 6 foot 2. An archer we are told. To stand in front of him is to feel a chill of the past and a sense of sadness for the loss of such a young man.

The carving is they think the name of the cook.

Again, so much to see and only a quick if still amazing surveying. I was exhausted and Heather and I retired to a pub, after a newly restored B-52 or something flew low above us, for a snack. I had a salad and a pint; she had a burrito, which amused me as we were about as far from the home of the burrito as could be possible here on the seaside of Portsmouth.

Then we took a train back to London--a cleaner version of Amtrak, with nice tables upon which to read the Guardian, or some such paper. I spent the time looking out the window at the suburbs, many of them not unlike places along the Hudson. Big houses and restaurants. It was after 8 thirty when we got back to the station and we were grateful for the cab to take us back to the Penn Club.

I had only one more full day in this astounding town in which I found myself so comfortable, and I would spend much of it walking and meeting up with Denise at her club, eating a lovely early dinner and then attending Mass at the Farm Street Catholic Church nearby, not far from Berkeley Square. And then we, she the lady of a certain age and me a somewhat younger lady of a certain age, joined the young English up and comers at a nearby pub. I had two pints, while she drank ginger ale, and realized that the English Beer is far more with alcoholic content than the average American beer.

The next day I would arrive at British Airways to find that they were overbooked, but somehow I managed to get on the flight, and on a bulkhead, tasking two Lorazepams and not being slightly calm as a result. Hypervigilant though I remained for 10 plus hours, it was a lovely quiet flight.

I was delighted to arrive home safely so I could share a few of the moments which so entranced me. It has taken me nearly the whole summer to write of the trip, and now, somehow, it seems so long ago.

I shall go back, I believe and this time, branch out to other places, like Ireland and France. Ireland first, I should think, where there are some members of my mother's family, we unknown to each other for now. I had the chance to go just this month, but there were many other things which made that difficult, and so I did not. The loss of a good friend and mentor, which was sad. And a new pair of 20 20 eyes (mine) which was a great revelation.

More to come from Los Angeles. . . .by way of Djinn from the Bronx!

Thursday, August 1, 2013

Conversion at Littlemore

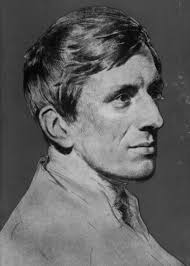

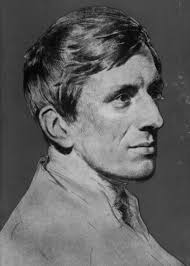

About three miles outside of Oxford is a quiet town that probably would remain largely unknown but for one of its former, brief, inhabitants, John Henry Newman.

In about 1841, after a long and nearly complete process of developing and embracing his Christian faith, Newman, former long time vicar of St. Mary the Nativity attached to Oriel College where he was a fellow, retreated to a smallish patch of land, its stable converted into cells for himself and those other searchers of the Oxford Movement, to read and to pray. And to continue his consideration of his next move, to the Roman Church which heretofore he had joined his religious colleagues in dismissive critique.

It was at the library in Littlemore that, having come to the difficult place that logic and faith, and his life long zeal for the intellectually and spiritually true led him, he converted from Anglicanism to Roman Catholicism. He was received by Dominic Barbieri, a Catholic priest who had come to know him. They used a large writing desk, which had a feature of being angled for holding books or writing while standing, or laid flat. Laid flat, it became an altar at which Barbieri celebrated Mass and Newman received his first Communion as a member of the Catholic Church. His conversion did not begin in this place, and he actually spent very few years here, but it was consummated there, and so there I wished to visit along with St. Mary's. The trifecta would have been the Birmingham Oratory, but I allowed the geography of my visit and spontaneity, perhaps even Providence itself, to guide whether I would get to any of them. I got to two and it was enough to inspire my re-reading of this Blessed man, on the way to sainthood, with the usual popular culture war being waged against him in secular fora.

There is no simple summation of the man or his writing. He was born in 1801 and died an old man in 1899. He had the gift of intellectual thought and tenacity to historical religious fact, meaning the history of the Christian Church. He would likely have preferred the answer to his queries to be different than they were.

His search took him from Evangelicalism, Calvinism, Low (Anglican) Church, and High. He wanted a new Reformation to make the Anglican Church, which he considered as having fallen into banal formality and confused doctrines (since Calvinism, Lutheranism and Henry VIII's version had all somehow merged for the convenience and private judgment of the respective believer) what it was meant to be, holy, catholic and apostolic, not mere form, but deep within the soul, a way of life for its very salvation. If indeed the Roman Church (rather cruelly denominated as Papists) had had their failings, as of course they did, causing schism--a rather narcissistic form of reform, rather than reform from within-- so now did the Anglicans, with comfortable prelates many of whom did not even believe the Anglican dogmas, to the extent it was entirely agreed what they were needed to own up to failure. But to the extent that any teacher at Oxford believed that it was even necessary or desirable to concern themselves with the moral interior of a student, it was a delicate subject, for the school, best to be avoided.

Newman's loss of students to tutor in part because of his unfortunate views about the need for an educated religious man, allowed him to join and energize the incipient Oxford Movement, which wrote tracts on the varieties of subjects that Anglicans had stored away as quaint relics of old days.

Newman really did not want to admit of many things that the Roman Church articulated. I won't try to discuss the Real Presence, but there were distinct differences even here. Then there were the saints, and the Blessed Virgin Mary and not the least, the idea of Apostolic Succession. Newman was willing, for a long long time to tell himself that there had been no breach of it when Henry VIII (against the backdrop of other historical forces, like Luther and Calvin) made himself Supreme Head of the Church of England, in place of the Pope of Rome. All sorts of lofty rationales were given to that particular edict, but it was really quite simple. Catherine of Aragon, Henry's long time wife, bore him a daughter, Mary, no sons. She was quite a bit older and no sons were in the offing. Then there was Anne Boleyn, the picture of child bearing, boy bearing youth. The Catholic Church as a whole in England was indeed soft and in some, maybe many, like Cardinal Wolsey, self aggrandizing such that as Henry took pieces of their souls, they wobbled and warbled weak objections. They stood by as those who were strong opponents (Thomas More, but even more consistently in some ways, John Fisher) spoke out, and literally lost their heads. Oh, you've watched the Tudors; although some have said that it was inaccurate, I think after reading a bit here and there, it was more so than anyone might like. The Catholic Church did not stand strong, because human considerations got in the way (always the problem alas).

Ok, where was I? I am no historian. I am encapsulating what I have read, and, as of my visit to England, seen.

Newman wanted the Anglican Church to stay his church. And then he read the Church Fathers, the ones from a century to three centuries after Christ died, and he began to see that he could not rationalize that which had created the Anglican Church. To become a Catholic was to become alone. He had to give up his vicarages. He had to give up, in many cases, his friends, for years or forever. Even family with rare exception found him wanting in his choice. His time in the Catholic Church was rewarding he'd always say, but difficult too, for there too he found suspicion, those who would say that he was not sufficiently orthodox, despite the fact that his writings themselves spoke volumes of the clarity of his faith. Still, he was named Cardinal in the last year of his life. A kind of vindication for a man who truly discerned the Voice of God.

He has always fascinated me--his willingness to give up a safe and well regarded life with which he was familiar--in order to follow to the conclusion he did, which was not what he would have wanted when he began his search.

I just needed to go to Littlemore while I was in Oxford. Heather was kind enough to join me on what turned out to be a more difficult task of locating the "college". It isn't a "college" in the traditional sense. But it was a place that he went to to study and consider, and pray. He resisted, apparently, the idea of calling it a "retreat" house as well. The bus from Oxford deposited us at a building that looked like none of the pictures I had ever seen of the college. There was absolutely no one about and no one to ask for quite some time, but ultimately we found a sole person getting out of her car. We had been led mistakenly to the old age home for nuns. The woman gave us marginal directions and we finally found what looked to me the right place. But it was downright deserted it seemed. I wouldn't expect a bevy of tourists here, but Catholics are well aware of the place, and I would have anticipated at least 10 to 20 people on a short tour. There was no one. We walked up the few steps to the entry way, and I could tell from the bust of Newman on the small garden ground brimming with wisteria, that we were in the right place but I saw no one. I heard voices from what would have been one of the cells of the men who once stayed and prayed there, and I walked in to see various women and a man preparing for what I assumed was some kind of raffle.

I asked if this was the right place, though I thought so. "Oh, yes." "I am from America and I was hoping to take a look around."

"Oh, of course, just go back where you came in and ring the box. Sr. Bridget will answer and I'm sure she'll take you around."

I apparently was the only tourist at least this day. Sr. Bridget was a beautiful (without makeup that is something) young nun. I asked about my being the only person. She said that up to here their weather had been bad (England had had rain of 50 days just prior to my visit, but it was beautiful most of my time there), and they usually get most of their visitors in the summer, about 2,000 a year.

So, we began with the library. I have seen several DVDs about Littlemore and the Birmingham Oratory and I recognized the long narrowish room. Much has been recreated, in that all of Newman's original books are now in the Oratory. But the desk was there, the makeshift altar. They were delighted to have gotten this back. I tried to imagine that private, first Mass for Newman in his new, hard won faith. I wanted to touch it. I did not. And then she took me to his room, also in many ways, recreated, with this or that piece of furniture that had been his, and including a few relics of the priest that received him. The floor, I was told, was the same floor that Newman had walked on as he went to pray or to his bed. I have always liked, in my few travels, trodding where others have long before me, and to stand here, where no doubt Newman paced from time to time, when he could not sleep, which doubtless he could not as he considered his grand and dangerous action, was touching.

And then she took me to the chapel. When he was living as an Anglican there, there would have been no Blessed Sacrament. But now, of course there is. And surely, he prayed in this room. Cor ad Cor Loquitur is his motto, Heart Speaks to Heart. Sister asked if I'd like to be alone for a bit, to pray. Heather was so accommodating and happy to rest in the garden after our significant walking. Yes. I would love to. It is also a small room, with a small altar, and red drapes surround it and a few pews on either side. To be in the back was still to be close.

I felt something. I don't know what exactly. Emotional, certainly. There were tears in my prayers. An intimacy, something with which I generally am not comfortable, but in that room I felt embraced by the intercessor John Henry Newman and by our God whose ear he has.

I heard only the birds in the garden against the matte of silence. Would this change me in some way? I hoped so. Would it make whatever it is I am discerning more palpable to me, something I would not run from? I didn't know. I decided just to be in that moment of history, a saint, and the Presence of God.

When I went back to the library, I had to let Sister Bridget know, so she could lock up the Chapel. I asked her where I could put the money for anything, mostly literature, that I might take. "Oh, there's a little metal box." The trust of the holy.

Later, I would go to St. Mary of the Nativity to see where many of the Parochial and Plain Sermons for which Newman remains famous were preached. It was once the University Church and is attached to Oriel College, where Newman was fellow. There was no obvious sign of him, nothing heralding that it was here he had preached. This remains an Anglican Church, and it is Cranmer, a martyr for his faith, at the hands of Mary, Henry's once banished daughter, and half sister of Elizabeth. Mary was Catholic. Elizabeth was not. Mary tried to undo the work of her father. It was not only too late, but her methods were obviously questionable, at least in modern terms. But as I wandered around the pulpit, the high pulpit, on which I knew he had stood, I saw a bronze like placque with his face in profile. It gently noted that he had preached here.

There have been many books about Newman's life and choices, Ian Ker is one. And most recently "Passion for Truth" by Fr. Juan Velez.

In a world that now views truth as relative, or imposed by relentless media assaults and word games or a government which would deny, despite the words "In God We Trust" chiseled on the walls of Congress; in a world that insists God and his natural law had nothing to do with the existence of the United States, the idea that what Newman sought, and found, was TRUTH, is an opportunity for a good chortle by those that control our paths of information, in fact, our lives.

We think we are better, more well informed, more given to good, and reason, and fair play than our forbears. Here is something that Newman said about that in Sermon 7, Sins of Ignorance and Weakness.

...Consider our present condition, as shown in Scripture. Christ has not changed this, though He has died; it is as it was from the beginning--I mean our actual state as men. We have Adam's nature in the same sense as if redemption had not come to the world. It has come to all the world, but the world is not changed thereby as a whole,-that change is not a work done and over in Christ. We are changed one by one, the race of man is what it ever was, guilty--what it was before Christ came, with the same evil passions, the same slavish will. The history of redemption if it is to be effectual must begin from the beginning with every individual of us and must be carried on through our own life. It is not a work done ages before we were born. We cannot profit by the work of a Saviour though He be the Blessed Son of God so as to be saved thereby without our own working for we are moral agents, we have a will of our own and Christ must be formed in us and turn us from darkness to light, if God's gracious purpose, fulfilled upon the cross is to be in our case more than a name, an abused, wasted privilege. , ,

For me, though, this was a small personal pilgrimage, for which I remain enormously grateful. With God, there are no accidents.

(Please note that the photos are from the Newman Friends International site; my photos were among those I accidentally deleted. I have had the feeling that this was not an accident; that I was to experience, not photograph.)

In about 1841, after a long and nearly complete process of developing and embracing his Christian faith, Newman, former long time vicar of St. Mary the Nativity attached to Oriel College where he was a fellow, retreated to a smallish patch of land, its stable converted into cells for himself and those other searchers of the Oxford Movement, to read and to pray. And to continue his consideration of his next move, to the Roman Church which heretofore he had joined his religious colleagues in dismissive critique.

It was at the library in Littlemore that, having come to the difficult place that logic and faith, and his life long zeal for the intellectually and spiritually true led him, he converted from Anglicanism to Roman Catholicism. He was received by Dominic Barbieri, a Catholic priest who had come to know him. They used a large writing desk, which had a feature of being angled for holding books or writing while standing, or laid flat. Laid flat, it became an altar at which Barbieri celebrated Mass and Newman received his first Communion as a member of the Catholic Church. His conversion did not begin in this place, and he actually spent very few years here, but it was consummated there, and so there I wished to visit along with St. Mary's. The trifecta would have been the Birmingham Oratory, but I allowed the geography of my visit and spontaneity, perhaps even Providence itself, to guide whether I would get to any of them. I got to two and it was enough to inspire my re-reading of this Blessed man, on the way to sainthood, with the usual popular culture war being waged against him in secular fora.

There is no simple summation of the man or his writing. He was born in 1801 and died an old man in 1899. He had the gift of intellectual thought and tenacity to historical religious fact, meaning the history of the Christian Church. He would likely have preferred the answer to his queries to be different than they were.

His search took him from Evangelicalism, Calvinism, Low (Anglican) Church, and High. He wanted a new Reformation to make the Anglican Church, which he considered as having fallen into banal formality and confused doctrines (since Calvinism, Lutheranism and Henry VIII's version had all somehow merged for the convenience and private judgment of the respective believer) what it was meant to be, holy, catholic and apostolic, not mere form, but deep within the soul, a way of life for its very salvation. If indeed the Roman Church (rather cruelly denominated as Papists) had had their failings, as of course they did, causing schism--a rather narcissistic form of reform, rather than reform from within-- so now did the Anglicans, with comfortable prelates many of whom did not even believe the Anglican dogmas, to the extent it was entirely agreed what they were needed to own up to failure. But to the extent that any teacher at Oxford believed that it was even necessary or desirable to concern themselves with the moral interior of a student, it was a delicate subject, for the school, best to be avoided.

Newman's loss of students to tutor in part because of his unfortunate views about the need for an educated religious man, allowed him to join and energize the incipient Oxford Movement, which wrote tracts on the varieties of subjects that Anglicans had stored away as quaint relics of old days.

Newman really did not want to admit of many things that the Roman Church articulated. I won't try to discuss the Real Presence, but there were distinct differences even here. Then there were the saints, and the Blessed Virgin Mary and not the least, the idea of Apostolic Succession. Newman was willing, for a long long time to tell himself that there had been no breach of it when Henry VIII (against the backdrop of other historical forces, like Luther and Calvin) made himself Supreme Head of the Church of England, in place of the Pope of Rome. All sorts of lofty rationales were given to that particular edict, but it was really quite simple. Catherine of Aragon, Henry's long time wife, bore him a daughter, Mary, no sons. She was quite a bit older and no sons were in the offing. Then there was Anne Boleyn, the picture of child bearing, boy bearing youth. The Catholic Church as a whole in England was indeed soft and in some, maybe many, like Cardinal Wolsey, self aggrandizing such that as Henry took pieces of their souls, they wobbled and warbled weak objections. They stood by as those who were strong opponents (Thomas More, but even more consistently in some ways, John Fisher) spoke out, and literally lost their heads. Oh, you've watched the Tudors; although some have said that it was inaccurate, I think after reading a bit here and there, it was more so than anyone might like. The Catholic Church did not stand strong, because human considerations got in the way (always the problem alas).

Ok, where was I? I am no historian. I am encapsulating what I have read, and, as of my visit to England, seen.