In about 1841, after a long and nearly complete process of developing and embracing his Christian faith, Newman, former long time vicar of St. Mary the Nativity attached to Oriel College where he was a fellow, retreated to a smallish patch of land, its stable converted into cells for himself and those other searchers of the Oxford Movement, to read and to pray. And to continue his consideration of his next move, to the Roman Church which heretofore he had joined his religious colleagues in dismissive critique.

It was at the library in Littlemore that, having come to the difficult place that logic and faith, and his life long zeal for the intellectually and spiritually true led him, he converted from Anglicanism to Roman Catholicism. He was received by Dominic Barbieri, a Catholic priest who had come to know him. They used a large writing desk, which had a feature of being angled for holding books or writing while standing, or laid flat. Laid flat, it became an altar at which Barbieri celebrated Mass and Newman received his first Communion as a member of the Catholic Church. His conversion did not begin in this place, and he actually spent very few years here, but it was consummated there, and so there I wished to visit along with St. Mary's. The trifecta would have been the Birmingham Oratory, but I allowed the geography of my visit and spontaneity, perhaps even Providence itself, to guide whether I would get to any of them. I got to two and it was enough to inspire my re-reading of this Blessed man, on the way to sainthood, with the usual popular culture war being waged against him in secular fora.

There is no simple summation of the man or his writing. He was born in 1801 and died an old man in 1899. He had the gift of intellectual thought and tenacity to historical religious fact, meaning the history of the Christian Church. He would likely have preferred the answer to his queries to be different than they were.

His search took him from Evangelicalism, Calvinism, Low (Anglican) Church, and High. He wanted a new Reformation to make the Anglican Church, which he considered as having fallen into banal formality and confused doctrines (since Calvinism, Lutheranism and Henry VIII's version had all somehow merged for the convenience and private judgment of the respective believer) what it was meant to be, holy, catholic and apostolic, not mere form, but deep within the soul, a way of life for its very salvation. If indeed the Roman Church (rather cruelly denominated as Papists) had had their failings, as of course they did, causing schism--a rather narcissistic form of reform, rather than reform from within-- so now did the Anglicans, with comfortable prelates many of whom did not even believe the Anglican dogmas, to the extent it was entirely agreed what they were needed to own up to failure. But to the extent that any teacher at Oxford believed that it was even necessary or desirable to concern themselves with the moral interior of a student, it was a delicate subject, for the school, best to be avoided.

Newman's loss of students to tutor in part because of his unfortunate views about the need for an educated religious man, allowed him to join and energize the incipient Oxford Movement, which wrote tracts on the varieties of subjects that Anglicans had stored away as quaint relics of old days.

Newman really did not want to admit of many things that the Roman Church articulated. I won't try to discuss the Real Presence, but there were distinct differences even here. Then there were the saints, and the Blessed Virgin Mary and not the least, the idea of Apostolic Succession. Newman was willing, for a long long time to tell himself that there had been no breach of it when Henry VIII (against the backdrop of other historical forces, like Luther and Calvin) made himself Supreme Head of the Church of England, in place of the Pope of Rome. All sorts of lofty rationales were given to that particular edict, but it was really quite simple. Catherine of Aragon, Henry's long time wife, bore him a daughter, Mary, no sons. She was quite a bit older and no sons were in the offing. Then there was Anne Boleyn, the picture of child bearing, boy bearing youth. The Catholic Church as a whole in England was indeed soft and in some, maybe many, like Cardinal Wolsey, self aggrandizing such that as Henry took pieces of their souls, they wobbled and warbled weak objections. They stood by as those who were strong opponents (Thomas More, but even more consistently in some ways, John Fisher) spoke out, and literally lost their heads. Oh, you've watched the Tudors; although some have said that it was inaccurate, I think after reading a bit here and there, it was more so than anyone might like. The Catholic Church did not stand strong, because human considerations got in the way (always the problem alas).

Ok, where was I? I am no historian. I am encapsulating what I have read, and, as of my visit to England, seen.

Newman wanted the Anglican Church to stay his church. And then he read the Church Fathers, the ones from a century to three centuries after Christ died, and he began to see that he could not rationalize that which had created the Anglican Church. To become a Catholic was to become alone. He had to give up his vicarages. He had to give up, in many cases, his friends, for years or forever. Even family with rare exception found him wanting in his choice. His time in the Catholic Church was rewarding he'd always say, but difficult too, for there too he found suspicion, those who would say that he was not sufficiently orthodox, despite the fact that his writings themselves spoke volumes of the clarity of his faith. Still, he was named Cardinal in the last year of his life. A kind of vindication for a man who truly discerned the Voice of God.

He has always fascinated me--his willingness to give up a safe and well regarded life with which he was familiar--in order to follow to the conclusion he did, which was not what he would have wanted when he began his search.

I just needed to go to Littlemore while I was in Oxford. Heather was kind enough to join me on what turned out to be a more difficult task of locating the "college". It isn't a "college" in the traditional sense. But it was a place that he went to to study and consider, and pray. He resisted, apparently, the idea of calling it a "retreat" house as well. The bus from Oxford deposited us at a building that looked like none of the pictures I had ever seen of the college. There was absolutely no one about and no one to ask for quite some time, but ultimately we found a sole person getting out of her car. We had been led mistakenly to the old age home for nuns. The woman gave us marginal directions and we finally found what looked to me the right place. But it was downright deserted it seemed. I wouldn't expect a bevy of tourists here, but Catholics are well aware of the place, and I would have anticipated at least 10 to 20 people on a short tour. There was no one. We walked up the few steps to the entry way, and I could tell from the bust of Newman on the small garden ground brimming with wisteria, that we were in the right place but I saw no one. I heard voices from what would have been one of the cells of the men who once stayed and prayed there, and I walked in to see various women and a man preparing for what I assumed was some kind of raffle.

I asked if this was the right place, though I thought so. "Oh, yes." "I am from America and I was hoping to take a look around."

"Oh, of course, just go back where you came in and ring the box. Sr. Bridget will answer and I'm sure she'll take you around."

I apparently was the only tourist at least this day. Sr. Bridget was a beautiful (without makeup that is something) young nun. I asked about my being the only person. She said that up to here their weather had been bad (England had had rain of 50 days just prior to my visit, but it was beautiful most of my time there), and they usually get most of their visitors in the summer, about 2,000 a year.

So, we began with the library. I have seen several DVDs about Littlemore and the Birmingham Oratory and I recognized the long narrowish room. Much has been recreated, in that all of Newman's original books are now in the Oratory. But the desk was there, the makeshift altar. They were delighted to have gotten this back. I tried to imagine that private, first Mass for Newman in his new, hard won faith. I wanted to touch it. I did not. And then she took me to his room, also in many ways, recreated, with this or that piece of furniture that had been his, and including a few relics of the priest that received him. The floor, I was told, was the same floor that Newman had walked on as he went to pray or to his bed. I have always liked, in my few travels, trodding where others have long before me, and to stand here, where no doubt Newman paced from time to time, when he could not sleep, which doubtless he could not as he considered his grand and dangerous action, was touching.

And then she took me to the chapel. When he was living as an Anglican there, there would have been no Blessed Sacrament. But now, of course there is. And surely, he prayed in this room. Cor ad Cor Loquitur is his motto, Heart Speaks to Heart. Sister asked if I'd like to be alone for a bit, to pray. Heather was so accommodating and happy to rest in the garden after our significant walking. Yes. I would love to. It is also a small room, with a small altar, and red drapes surround it and a few pews on either side. To be in the back was still to be close.

I felt something. I don't know what exactly. Emotional, certainly. There were tears in my prayers. An intimacy, something with which I generally am not comfortable, but in that room I felt embraced by the intercessor John Henry Newman and by our God whose ear he has.

I heard only the birds in the garden against the matte of silence. Would this change me in some way? I hoped so. Would it make whatever it is I am discerning more palpable to me, something I would not run from? I didn't know. I decided just to be in that moment of history, a saint, and the Presence of God.

When I went back to the library, I had to let Sister Bridget know, so she could lock up the Chapel. I asked her where I could put the money for anything, mostly literature, that I might take. "Oh, there's a little metal box." The trust of the holy.

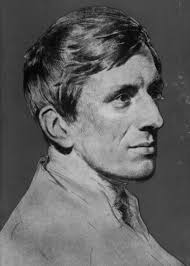

Later, I would go to St. Mary of the Nativity to see where many of the Parochial and Plain Sermons for which Newman remains famous were preached. It was once the University Church and is attached to Oriel College, where Newman was fellow. There was no obvious sign of him, nothing heralding that it was here he had preached. This remains an Anglican Church, and it is Cranmer, a martyr for his faith, at the hands of Mary, Henry's once banished daughter, and half sister of Elizabeth. Mary was Catholic. Elizabeth was not. Mary tried to undo the work of her father. It was not only too late, but her methods were obviously questionable, at least in modern terms. But as I wandered around the pulpit, the high pulpit, on which I knew he had stood, I saw a bronze like placque with his face in profile. It gently noted that he had preached here.

There have been many books about Newman's life and choices, Ian Ker is one. And most recently "Passion for Truth" by Fr. Juan Velez.

In a world that now views truth as relative, or imposed by relentless media assaults and word games or a government which would deny, despite the words "In God We Trust" chiseled on the walls of Congress; in a world that insists God and his natural law had nothing to do with the existence of the United States, the idea that what Newman sought, and found, was TRUTH, is an opportunity for a good chortle by those that control our paths of information, in fact, our lives.

We think we are better, more well informed, more given to good, and reason, and fair play than our forbears. Here is something that Newman said about that in Sermon 7, Sins of Ignorance and Weakness.

...Consider our present condition, as shown in Scripture. Christ has not changed this, though He has died; it is as it was from the beginning--I mean our actual state as men. We have Adam's nature in the same sense as if redemption had not come to the world. It has come to all the world, but the world is not changed thereby as a whole,-that change is not a work done and over in Christ. We are changed one by one, the race of man is what it ever was, guilty--what it was before Christ came, with the same evil passions, the same slavish will. The history of redemption if it is to be effectual must begin from the beginning with every individual of us and must be carried on through our own life. It is not a work done ages before we were born. We cannot profit by the work of a Saviour though He be the Blessed Son of God so as to be saved thereby without our own working for we are moral agents, we have a will of our own and Christ must be formed in us and turn us from darkness to light, if God's gracious purpose, fulfilled upon the cross is to be in our case more than a name, an abused, wasted privilege. , ,

For me, though, this was a small personal pilgrimage, for which I remain enormously grateful. With God, there are no accidents.

(Please note that the photos are from the Newman Friends International site; my photos were among those I accidentally deleted. I have had the feeling that this was not an accident; that I was to experience, not photograph.)